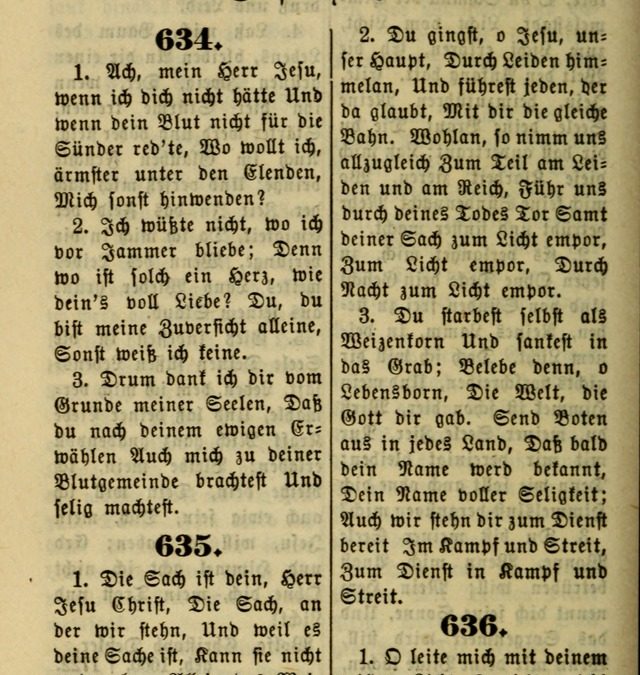

# 634 in the German Mennonite songbook in the photo above is Ach Mein Herr Jesu, Wenn Ich Dich Nicht Hätte. It was my father’s favorite hymn, and we sang it often as a family. When I hear it today, seventeen years after his death, I feel my dad’s presence more strongly than at any other time. And I am flooded with emotions.

This isn’t surprising, really. It turns out that music activates some of the same reward systems in the brain that are stimulated by food, sex and addictive drugs.

Of course, I know that Ach Mein Herr Jesu does nothing to stimulate emotions for you (unless you grew up in a German Mennonite church like I did). Music that touches us is intrinsically linked to our unique history.

Neuroscientists have shown us that music, memory and emotion are interconnected in fascinating ways. Musical emotions and musical memory can survive long after other forms of memory have disappeared, partly because listening to music engages many parts of the brain, triggering connections and creating associations.

Historically, researchers believed that classical music increased brain activity for all listeners, producing something called the Mozart effect. We now know that our brains are more nuanced than that, responding distinctively to the music we grew up listening to. It turns out, whether it’s a German Mennonite hymn, rock ’n’ roll, jazz, or a classical piece, our brains respond to what is part of our own unique background.

My guest on this week’s podcast episode is Doug Bradley, a Vietnam veteran who has spent over a decade using the music of the 1960s and 1970s to welcome home the men and women who served in that divisive Southeast Asian war and have never felt welcomed back.

Doug said, “When you bury those feelings for 40 or 50 years and boom, the song is there, whether it’s “Dock of the Bay,” whether it’s “We Gotta Get Out of this Place,” or it’s “Who’ll Stop the Rain,” there’s a trigger, and the floodgates open. For these men and women, because it hadn’t been expressed, all of Vietnam came out in that song, in that moment, in that sharing.”

Doug’s music project with veterans suggests that the evocative power of music goes well beyond stirring up emotions at the individual level. The music during the Vietnam era became a strong connective tissue. In his words, “Whether you stayed or whether you served, whether you participated or whether you protested, you heard the same songs, Creedence, Jimi Hendrix, Peter Paul and Mary …”

Shared music affects our tendency to connect with one another by impacting brain circuits involved in empathy, trust and cooperation. Maybe this explains why collective music making has been important in every culture around the world, and as far back as the hunting/gathering stage of human development. More than 30,000 years ago early humans were already playing bone flutes, percussive instruments and jaw harps. Even during a time when basic survival was at stake, making music was important enough to take time away from doing what was needed to survive — or perhaps collective music making actually was (and still is) required for survival.

Studies have also found that social cohesion is greater within families where children have a history of listening to music or singing together, and this effect holds across cultures where interdependence is more or less valued.

So yes, when I hear my father’s favorite hymn today, I am engulfed in emotions. And I feel bonded to family members that I’m otherwise not that connected to these days. It’s the song that brings me home.

What song brings you home?

As someone who lived through that era I sure am pulled toward a feeling of home by the music of those times—Creedence especially.