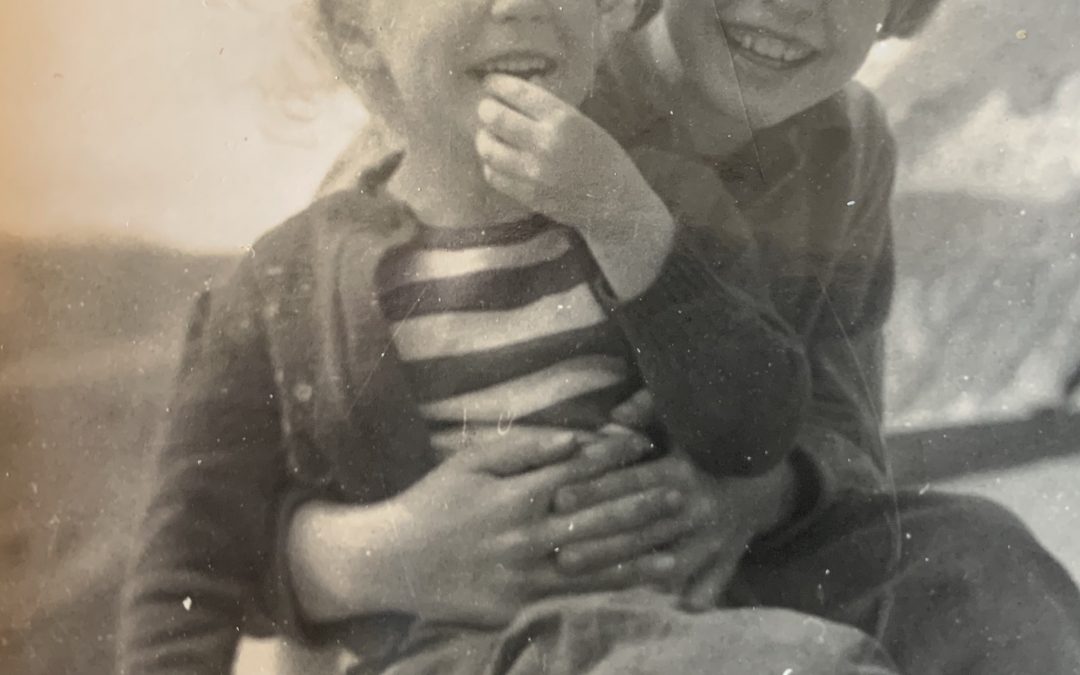

My Sister Mary Lou and I – She’s the Cute Little Curly-Haired Blond

I’m pleased to bring you the thinking of Mary Lou Bonham, a psychotherapist who also happens to be my sister. She and I will talk among other things about what it was like growing up on a Low-German Mennonite leprosy station in Paraguay, South America. Our parents were medical missionaries who did heroic things in the world, like revolutionizing how leprosy is treated on the planet today. But there are always costs associated with greatness it seems, and some of those costs we bore as their kids.

Despite our similar parentage and history, Mary Lou’s story is actually quite different than mine. We each found our own distinctive path toward healing. And as a professional psychotherapist, she helps us understand some of the reasons why this was the case and what we can all learn from it.

You can listen to the full conversation by clicking ‘play’ below, or on the following podcast platforms:

Love Endures

The following is a taste of my conversation with Mary Lou.

Q: How did growing up with German, Paraguayan and North American identities influence how you understand who you are?

Mary Lou: Those of us who grow up with multiple identities are very comfortable in many places, but not at home anywhere.

Q: What does reconciliation mean to you?

Mary Lou: Self-abandonment is never the path forward toward reconciliation. In order to truly reconcile with another, you must bring your whole self forward. And that may be so difficult that a relationship is hardly possible. It may be very limited because it depends on the capacity of both parties. The depth that you can achieve through reconciliation is not within your control alone.

Q: What was at the root of our father’s frequent bursts of anger?

Mary Lou: I think we have two basic ways in which our needs can be met. One is through vulnerably asking for help and support. The other is through power and control. Our father was incapable of being vulnerable, so control was his go-to. Anger is a very powerful tool when you’re trying to control your environment.

Q: How do you understand the role of crises in our lives?

Mary Lou: We all hate crises. Crises suck. They’re the worst. But they’re also transformative. So, they are a gift. If I had not hit rock bottom in my life, I think I would have had to limp along for a very long time with all of my stuff, and maybe slowly I could have worked through it. But the full-on crisis was transformative.

When asked if there’s one last thing she’d like our listeners to hear, Mary Lou says, “There is a quote from one of the saints that says, ‘All is well, and all is well, and all manner of things will be well.’ If all things are not well, it is not yet the end.”

About Mary Lou Bonham

Mary Lou is a multi-lingual psychotherapist based in Portland, Oregon. She also happens to be my sister. She and I grew up on a Low-German Mennonite leprosy station in Paraguay, South America. Our parents were medical missionaries who did heroic things in the world, like revolutionizing how leprosy is treated on the planet today. But there are always costs associated with greatness it seems, and some of those costs we bore as their kids.

Despite our similar parentage and history, Mary Lou’s story is actually quite different than mine. We each found our own distinctive path toward healing.

Find Mary Lou:

maryloubonhamcounseling.com

Book Mentioned in the Interview:

Love Is Complicated: A True Story of Brokenness and Healing, by Marlena Fiol, which is now available for pre-order on Amazon.

About Marlena Fiol, PhD

Marlena Fiol, PhD, is a globally recognized author, scholar and speaker. She is a spiritual seeker whose work explores the depths of who we are and what’s possible in our lives. Her significant body of publications on the topic, coupled with her own raw identity-changing experiences, makes her uniquely qualified to write about personal transformational change. She is also a certified tai chi instructor and freelance writer whose most recent work has appeared in numerous literary magazines and newsletters.

You can find Marlena in the following places:

https://marlenafiol.com

Facebook

Twitter: @marlenafiol

Podcast Transcript

Below is a complete transcript of the podcast. I used a transcription service to create this, please note that there may be errors. For a 100% accurate quote of what was said, please listen to the podcast itself via the links above.

Interviewer: Today I have a very special guest. Her name is Mary Lou Bonham and she’s my sister.

Mary Lou: Hello.

Interviewer: Mary Lou has agreed to join me in this episode to talk among other things about what it was like growing up on a low German Mennonite leprosy station in Paraguay, South America. Our parents were medical missionaries who did heroic things in the world, like revolutionizing how leprosy is treated on the planet today. But there are always costs associated with greatness it seems, and some of those costs we bore as their kids. But we’ll get to that.

The theme running through all of the episodes of this podcast season titled “Becoming who you truly are,” is that going through adversity sometimes leads us to more fully understand who we are and what’s possible for us. Mary Lou and I grew up in the same environment and each of us went through some dark nights of the soul before we began our healing journeys.

What I think will make this conversation interesting to our listeners is that with all of our similar parentage and history, her story is actually quite different than mine. We each found our own distinctive path. And as a bonus, Mary Lou is a professional psychotherapist, so she can help us understand some of the reasons why this was the case and what we can all learn from it. Mary Lou, welcome.

Mary Lou: Thank you.

Interviewer: Can you describe for our listeners who may not be familiar with what it means to be missionary kids, which we refer to as MKs, what that means and a bit about your own experience as an MK.

Mary Lou: So a term that maybe other people are familiar with, I don’t know, but it’s a term out there is third culture kids. So it refers to having grown up, the third culture means that I’ve grown up in a culture different from the culture of my family of origin and different from sort of what’s an at-home culture for them and are different.

So that encompasses more than just missionaries. Often military kids fall under that. So there’s that piece of third culture kids which has its gifts and the experiences and, you know, but I would say that the difficulties of it are that there’s lots of separation and grief, lots of goodbyes, multiple experiences of loss. There is the experience of having multiple identities. So growing up as a kid, being able to, because you are a kid you can sponge up whatever culture you’re part of is how we’re designed to do. And if we’re a part of different cultures, we sponge up all of them.

So we have these multiple identities and as a result we’re very comfortable in many places but not at home anywhere. And often we struggle with identity questions because who are we at the end of the day because that’s so defined by our growing up culture.

Interviewer: Absolutely.

Mary Lou: So that’s the third culture piece of being an MK. We had another layer which was the Mennonite piece, which was certainly a strand that connected across the various cultures. Although being Mennonite in Paraguay, of course, was very different than being Mennonite in Kansas but there were elements that were consistent across, you know. So, in some ways, I feel like my most at home culture is really Mennonite.

And then I would say the other piece that MKs have that maybe is a little bit like military, but probably not in the same way, is that parents of MKs are very often given to a mission that’s sort of this call of God, which is sacred and above all and overrides any other call in life, including your family and your children. And so, that’s the other element of being an MK that I think is impactful. So that’s kind of how I would separate or would talk about it.

Interviewer: Yeah. Mary Lou, I remember our father being angry a lot of the time. As you look back on it now as a therapist, what drove that anger?

Mary Lou: It’s an interesting question. There’s a lot I would say to that. Culturally, certainly, the history and then our dad’s own growing up experiences were like, there was a lot of adversity. And, you know, he talks about having a team of mules at age nine that he was in charge of. I look at my nine-year-old granddaughter and I think that’s just crazy, you know. And there was no, in low German we would say, we’re not gonna [foreign 00:05:26]. We’re not gonna baby you, you’re gonna have to do this thing, and there’s no if ands or buts about it. You just do it. And that kind of I think approach that is cultural, and also then reinforced in his own experience, I think underlies like his approach to all barriers.

Just part of what made him an amazing, like, you know, like a pioneer was this hard-headed encounter the barriers, you just bully your way through any barrier. And, you know, I just thought a few stories would be that came up. When I was a teenager, you know, we lived in [inaudible 00:06:11]. You will remember the terrible muddy roads and the floods we would have. And there was a time when one of these bridges, which is just two large planks across the river that you have to hit with your tires. There was like probably an inch of water flowing over them so you couldn’t see exactly where they were and you’re slipping and sliding your way.

And we got out, I think it was my mom and I got out and we carefully walked across, you know, this and then dad was determined to drive his car across despite there were multiple people around there like, and I don’t know if there were some trucks or something that were trying to get across. He’s just got into the car, put it into drive and charged across that and he didn’t make it. He slipped off and ultimately people, literally, there were men there that lifted the car back up onto the planks. But I remember standing on the edge watching him and I pictured myself diving into the river to go save him because I thought he was gonna drown.

I was picturing him, you know, but it was that kind of, or like when we would go to the trans-Chaco and there was this muddy slippery road that when it rained, the gates would close. And there were these outposts where there were people in charge of opening and closing these gates. And he would get this look in his eye and he would put his hat and pull it down and he would walk toward them and there wasn’t going to be any way that gate was not going to open for him. He was just going to get through there. That was his personality, it would just like kick in. And I think that we kids, you know, because we were kids, would get in the way. We wouldn’t somehow meet whatever he needed at that moment from us. And that’s how you address any barriers is you just push them out of the way, you know, sheer force.

Interviewer: So what was your strategy as a child to cope with that?

Mary Lou: Yeah, I wanted to say one more thing about that in a more sort of psychological way just to explain that.

Interviewer: Please.

Mary Lou: So I believe that dad, and with any human, I think we have two basic ways in which our needs can be met. One is through vulnerability and asking for help and support, and the other is through power and control. Those are the two ways I think fundamentally that we go about getting our needs met.

And you could probably add, you know, but I would say dad, because of this toughness, vulnerability was not an option. We never heard him say I’m sorry. We didn’t hear him acknowledge how he might’ve hurt us or vulnerability, you know, because in a different day and time, vulnerability, you know, he was in survival mode when he grew up. And vulnerability was not welcomed, it wasn’t ever modeled. It wasn’t anything he ever knew. So control was his go-to. Like that’s how you handle anything. And I think anger is a very powerful tool when you’re trying to control your environment. People respond to anger and fear gets people get you what you need.

Interviewer: Lined up.

Mary Lou: So, yeah. So just to say that’s how I kind of understand I guess that piece. We all had different ways of coping with it, and I would say this is where family systems kind of comes into play where when you have any kind of, and you know, addiction can do this at the heart of a family system when you have an anger thing going on, anger that can get triggered.

And it was, you know, the thing about it was he wasn’t angry all the time. I have lots of memories of him not being angry, but it was unpredictable. And then that’s like an alcoholic kind of family is like you don’t ever, you get good at sort of reading the room and figuring out, like you kind of have to always be a little bit hypervigilant because you don’t know when it’s going to come out. And so it’s that dynamic. That’s why it’s so significant, even though it doesn’t happen all the time, it kind of runs the show because everyone’s fearful and nervous about that anger.

So I would say, you know, we have our family organized around that and that’s where birth order I think is really important. And I would say probably likely your way of responding of being the lightning rod kid probably allowed me quite a bit of, you know, I dealt with it, so I’ll just say I dealt with it by trying to please my dad. I adored him. I wanted his approval more than anything in the whole wide world, I would have done anything for him.

Interviewer: Save him at the bottom of the river.

Mary Lou: Yes. Right. And I mean, in any way, I just wanted his approval and his love. I just thought he walked on water. I mean, I just thought, well, not literally, but obviously I was worried about him sinking. But, yeah. And so, and the way that I handled the anger was I became very good at flying under the radar and just be a good girl, as good as you can be.

Interviewer: Yeah. Whereas mine was to get in his face, which led to a lot of beatings, yeah.

Mary Lou: And that’s where I think that because you were in his face, it worked much better for me to be under the radar because…

Interviewer: Yeah. Is this a pretty typical family narrative?

Mary Lou: Yes, absolutely. So you have kind of the jolly jokester, which David kind of became that, and you have the sort of rising star, like the person who’s like the success story, who rises up and becomes the model, like Wes I would say. And I mean you eventually also I think moved in that direction, but from well we all have our…but as kids I would say the you being the sort of in your face kid, me being kind of the lost child, that’s pretty typical of like an alcoholic family system.

And then you have a very codependent partner, which my mother was. She found her own ways to be powerful but it had to be very subtle. And she didn’t have any outright power, like straight up. She wouldn’t argue with dad because she wasn’t going to win that battle. And so she always was trying to be the peacekeeper. She’s trying to smooth things over and have things be good and happy and no problems. And however she could make it be that way, that was very important from her perspective is to have a peaceful, happy family which is again, really typical of like a family system in trouble.

Interviewer: So Mary Lou, as you know, the theme of this podcast season is that suffering sometimes leads us to personal growth that often maybe wouldn’t be possible otherwise for us. In my forthcoming book, I described my own brokenness as a doorway to my healing. Can you describe for us what led to your own suffering and to finally hitting rock bottom?

Mary Lou: I mean, there’s a lot of stories and all of that. I would say fundamentally, there’s dad’s anger but I would say fundamentally there was a failure of healthy attachment in our family, which led to a lot of big holes in our development. And it leaves us ill-equipped to handle the challenges of life. A piece of that for all of us was, you know, leaving home at an early age and I think a lot of my overt wounds happened kind of in that season. But I think underneath that was this kind of, you know, this sort of lack of resilience because of that attachment problem.

My deepest attachment I would say was to my sister, Lisa, who as you know, was 11 years older than I was. And I think she was in a vacuum, an attachment vacuum when I was born, and we became each other’s sort of answer to attachment needs. And so I would say my earliest, very big wound was at age three when we were separated. And I would say throughout my childhood and teenage years in my most depressed times. So I ended up with a lot of depression and I can say a little more about that, but it was this I wanted to kill myself but there was one person that would be devastated if I did that and that was Lisa. It wasn’t my parents. If you would’ve asked me, I would’ve said yes, of course, they love me, they love me so much. But in that deepest place of attachment, there was a sense of they wouldn’t care.

Interviewer: Life would go on.

Mary Lou: Life would go on. I mean, that was what I believed. Whether it was true or not, it is what my deepest place believed. And so it’s that attachment. I would say there were then added to that were many, there was a lot of grief. And the problem with the grief more than even the grief was that it was not seen or acknowledged. There was not a soul that witnessed that grief or validated it.

And what it looked like was the way I interpreted it as a kid and as a teen was if I were doing the right thing, if I were good enough, if I were truly grateful, I would not have these feelings. So it was shrouded in shame because I’m failing somehow and I can’t have pain because that would hurt my parents. That would detract from the mission and this overarching sense of God needing me to be this certain way or, you know, that if I really trusted God, I would be okay.

So that was the abandonment began, you know, with my sister. And then I would say then all throughout my middle school and high school years, each year I lived with a different person in a different circumstance. At that point, and this is birth order again, the parents were beginning to wake up to the fact that things [inaudible 00:18:40] you all, and that part of that was the message they’d gotten was like leaving us with other people wasn’t so good.

So ironically some of the big wounds were, I was settled with my sister Lisa in one of the best years throughout that time and they forced me to leave and move out to [inaudible 19:00], which was my most depressed year of all. So ironically, their attempt to somehow fix this still wasn’t attuning to what I needed or where I was at. They were just hauling me around, kind of. So I had severe bouts of depression that followed usually losses. The first one was when I was in eighth grade and then I remember being awake hours at night praying to die and nobody really witnessing that. And then again in my sophomore year of high school. So, yeah.

Interviewer: Thank you for so vulnerably telling the story because I know that a lot of listeners will identify with it, whether they share the circumstances or not, especially the shame that goes with those feelings of depression and fear and inadequacy. So thank you for that. So then you reached out for help at one point.

Mary Lou: Yeah, I did. So I ended up when my first year of college was another huge like dip into depression, anxiety. I feel like the pressures of developmentally of early adulthood were setting on, you know, like, who am I? Growing within me was this dissonance between who I had been told God was and my experiences, and sort of like, that’s the very foundation that I would always go back to is God in all of this and hanging onto that and that began to crumble.

And that was like the last straw. That’s the one thing that had probably kept me alive at different points of crisis in the past and that was beginning to fall apart. And I was, my questions just, my faith couldn’t withstand, well, I would say my faith, my very toxic beliefs at that time couldn’t withstand the questions that I was holding in my reality, which was, I’m told that this is a God of love that’s holding my life and the universe but man, this sucks. And I don’t feel that anywhere in the bones and at some point that just crumbled and I think all of those developmental holes just gave way.

And I had a roommate who basically just walked me to the local mental hospital, the therapeutic center, whatever. And I mean there was also some other, I got some validation and support from a professor at the college. It was maybe the first time that I began to disclose some of this and felt somebody witnessing it and validating it but that when I arrived there, they determined that they wanted to admit me for a week. And I remember feeling like shocked and I mean something like good, like I don’t know how the emotion is exactly to describe it, but like, oh my gosh, they’re not going to tell me this is fine, just be grateful and deal with it. I don’t know what I thought they were going to say but it was something like that.

And I just wanted to die, you know, and somebody said, I see that and we want you to stay here. We think you need help. I mean, just that thing of you need help, it’s just incredible. Somebody is like, they believe I need help, oh my gosh. I mean, it just seems crazy now but at the time, that was just such a foreign thought. And it was a transformative experience. Not really anything they did there except that I was validated and heard and there was some empathy. And I remember people even in the group sessions I was in saying, wow, you went through a lot and I was like, oh wow, I did. Oh my gosh. This isn’t normal like what I went through, you know. So, so powerful. And I guess that’s another lesson that I would hold forward is we hate crises. Crises suck. They’re the worst.

Interviewer: But they’re transformative.

Mary Lou: They are. They are essential, I think. I mean, they are a gift. Like I often looked at that week and if I had not hit that rock bottom, I think I would have had to limp along for a very long time with all of this stuff and maybe slowly could’ve worked through it, but the fact that it was such a full-on crisis and that like, I mean I remember it being like a dramatic experience to tell my parents, I spent a week in Prairie View. I am not okay. That took so much courage. So much courage. It was just breaking away from my role in the family, which was to be good, to be fine, to be happy, to be all of those things which I wasn’t. I was none of those things.

Interviewer: You were fortunate as one of the guests of this podcast season, Dr. Steven Post, said, and I think I’m quoting him, “You were one of the fortunate ones who was knocked to your knees.”

Mary Lou: Yes, and I have often said that. Often said that. That was a very fortunate for me kind of experience.

Interviewer: Yeah. Mary Lou, Dr. Larry Dossey, the author of “One Mind,” who’s also one of the guests in this podcast season, has said that we must all learn to forgive and forget in order to heal this planet and ourselves. Can you talk to us about what forgiveness means for you? Maybe most particularly around issues regarding our childhood family?

Mary Lou: I mean, I guess I would just say, for us as humans, those are some of the hardest forgiveness challenges because we come into the world as vulnerable human beings and at our core we really know that what we need and deserve is perfect parents. And when we don’t, when we encounter their wounds, it is extremely impactful, disorienting, painful.

So those are some of the hardest lessons of forgiveness, but I would say it is essential in all healing. I don’t think that we can get there without at some point confronting the need to forgive. But I think it’s very misunderstood and I would really, I have a lot of cautions around short-cutting the process of forgiveness because I think there’s a lot of things that are called forgiveness that aren’t really forgiveness and they can be toxic. And especially the more traumatized you’ve been, the more important it is to not go down the toxic paths of what may be labeled forgiveness. So I would just caution people when I say forgiveness is essential, I’m not talking about any kind of glib or forced or, you know, it’s deep. Forgiveness is deep, lifelong work and you cannot short circuit the process. You have to stay present to yourself.

Interviewer: Very challenging and well said.

Mary Lou: And so I would say the first part of forgiveness, and it could take years or forever, is that we have to see the truth with boldness. We have to bring our own truth forward. We have to be able to name what those pains and hurts were. It is simply not sugarcoating any of it. And until we can go to the depths of what that experience was, and I’m not talking about needing to, it’s not a path of blame primarily, it is a path of like blaming our parents and shitting on them. It’s not that. It’s coming to terms with what those wounds were, and how I experienced them, and being able to really be my own witness.

But most we need as humans to have others witness that. We can’t really do that all alone. I think that’s essential, that we need others to witness that in order for us to fully come into that truth. And then I would say the second part would be that we need to come to acceptance. And again, this is extremely difficult to understand that those who wounded us may not see or validate what they did to us. They’re not going to see that truth. They’re gonna deflect it, reject it, avoid it. They’re gonna have their own ways typically of…go ahead.

Interviewer: Yeah. They may never see it.

Mary Lou: They may never see it, or maybe they just see a small portion of it. And being able to come to acceptance around that, I think is really hard work also. And in my own faith tradition and in the Christian faith tradition, I would say that is the point at which there is cross bearing is required.

So in the image of Christ who took upon himself all of that anger and vitriol and toxicity and instead of passing it along to anyone else or throwing it back, he was crucified. And he said, “Father, forgive them. They don’t know what they do.” And I think at someplace we come to that place of cross-bearing, of being willing to bear that cross and to say, forgive them. They really didn’t know what they were doing.

And I think it’s extended to them this like you’re human, like I’m human. You did the best you could. Being able to kind of, to be able to release my own need for them to be a certain kind of parent for me. And you know, that’s a deep work of healing and for me, it’s very connected to a deep place of healing from a very divine source.

And for me, it comes in the image of Christ but I’ve seen that come in many different images for people. But I truly believe that there is full divine love that we can access and I cannot imagine how I could come to that place of forgiveness without that full, complete, kind of everything I needed love infusing my being in some very deep place that then equips me to be able to say, I am loved, I am held, I am safe. And out of this place I can say, I forgive you.

Interviewer: Yeah. That’s powerful. As you know, Mary Lou, my new book describes my own bumpy journey toward forgiveness and reconciliation. And especially important in that journey was the healing the wounds between our father and me and not surprising reconciliation is going to be the theme of my next podcast season. And just last week my husband, Ed, and I were speaking with friends about reconciliation. We began to explore important differences between forgiveness and reconciliation. In your view, what are some of those differences between forgiveness and reconciliation?

Mary Lou: That’s a very good distinction. It’s a very good distinction. I wanted to say one more thing if I could about forgive and forget kind of thing that I don’t know if you mentioned it or we’ve talked about it in the past. I would say it’s essential for me to not forget, and I’ll tell you why. It has to do with that truth-telling piece that my own inner child will never feel safe as long as I am not telling the truth about what she experienced.

In other words, maybe if I could reach some culmination of healing, I could not have to have that there. But certainly at this point, it’s like I am telling my inner child, you, you know, you little Mary Lou, I see what you experienced, and I am always going to be a safe place for you. I’m always gonna be a witness to that. I’m always gonna protect you. So that’s how I would just, you know, talk about the forgetting piece of forgiveness. It’s not about clinging to it in any kind of bitterness but it is a witness.

Interviewer: I do, I do understand. And I think in fact, that’s what you were referring to when you said don’t take the shortcuts. Go deep but go in, go looking boldly at the truth of what you and your little child experienced.

Mary Lou: Right. Yeah. And that will always be with you. We will always carry those things with us. And for me at least, it’s not helpful the language of trying to forget it, it’s much more of being very present to it in a compassionate way and moving on from that place. So, yeah. So what was your next question?

Interviewer: How do you perceive the difference between forgiveness and reconciliation?

Mary Lou: Right. I’d have so much to say theologically about all that.

Interviewer: Bottom line.

Mary Lou: Obviously reconciliation is two parties. Forgiveness, I can do from my own place and I can come to a place of full forgiveness. But if that other person isn’t extending something in my direction, I will have no hand to hold. It involves two parties. And I would say within that is there are times when reconciliation really will look very different than other times. I mean, for example, I would say if you want to talk about an extreme circumstance, let’s say you have somebody who’s extremely mentally ill, who’s your parent and you want to reconcile with them but they’re dysregulated, psychotic, you know, they might even want to kill you. It wouldn’t be safe or wise to sit down with that person and try to, you know, kind of build-up, kind of let’s just be and reconcile.

So safety I think is essential and it cannot happen in any form. It’s helpful to think about self-abandonment is never the path forward. So I will reconcile with you but I will bring my whole self forward. And that may be so difficult that a relationship is hardly possible. Maybe it’ll just be a Christmas card, you know, maybe it’ll just be some very limited because it depends on the capacity of both parties and the depth that you can go with reconciliation is not within your control alone. So yeah, that’s just I guess I would say that.

Interviewer: Yeah. You’ve often said love always wins. Can you define love as you’re using that term, when you say love always wins?

Mary Lou: So interesting that you say that because, you know, you had said that at the end of this interview, if there’s anything that I wanted to say, you know, what would it be? And it was that, that’s what I was going to say.

Interviewer: That’s great.

Mary Lou: That’s just great. I would say it wins in an enduring…love endures is maybe a better way to say it and, I mean, I guess wins. I mean, I believe in the ultimate final end of the equation. There is a quote from one of the saints that says, “All is well and all is well and all manner of things will be well.” And another way of somebody saying this was, all things will be well in the end. If all things are not well, it is not the end yet.

So that is a belief I have very deeply. I hold it as true as anything true could be in my life. It is my guiding center. It’s just despite, you know, and we haven’t hit the darkest of times in history, but we’re in a pretty dark time. And, you know, to be able to say, all will be well. And I just have had this deep voice of truth speak to me that I am holding you and you will be well. And I believe that is there for all of us and to me, it is the very source and essence of my life and of goodness and of joy, of beauty.

Interviewer: Yeah. What a wonderful way to end this conversation with you, Mary Lou. Thank you, my sister, for sharing yourself so generously with us.

Mary Lou: Oh, it’s always so wonderful to have these conversations with you and thank you so much.

Interviewer: I’ve been speaking with Mary Lou Bonham, a licensed Multilingual Psychotherapist in Portland, Oregon. Details about how to contact her can be found on the show notes. And thank you our listeners for joining us today. Please consider sharing this interview if you know of others who might be interested in the themes we explored. We are together on this journey.

Even though they came from the same family, Marlena and her sister Mary Lou each successfully found distinctive paths toward healing. I believe this provides a great example of the need to do the work of looking within ourselves to find our own distinctive path rather than trying to copy what we have heard about that has worked for others.

Thank you to you both for this interview. I remember you as children. I am reminded that I have a problem against my mother which I continue to try to forgive. She is gone but the problem remains.

Lydia, thank you so much for your authentic presence here! I wonder if Mary Lou remembers you or if she was too young…I remember you so well. And I love that we’re occasionally able to connect here.

Forgiveness is a lifelong challenge for all of us. I really appreciate Mary Lou’s perspective on it. And yours!

Marlena, such an interesting, thoughtful and loving conversation with your sister. My sister and I were fortunate to have been raised in a fun, loving and supportive family with doting grandparents living nearby. Our childhood was similar to a 1950s TV sitcom (Leave It to Beaver or Father Knows Best), but it wasn’t perfect. My sister and I fought. I cried myself to sleep if I heard my parents arguing. I thought my parents were too strict. But compared to a fearful and less-than-supportive household, I was blessed. I wish my parents were alive so that I could ask for forgiveness for my teenage years and the distancing of my early 20s. I wish I could dote on them now. But I know they loved me and they knew that I loved them. Luckily, we were all given time as adults to say the words.

Oh Jude, thank you for this! I love the glimpse you gave us of your childhood. And those last words…oh so powerful: “Luckily, we were all given time as adults to say the words.”

We were both blessed with being given that time.