Welcome to Our New Series:

Choosing Compassion Over Fear

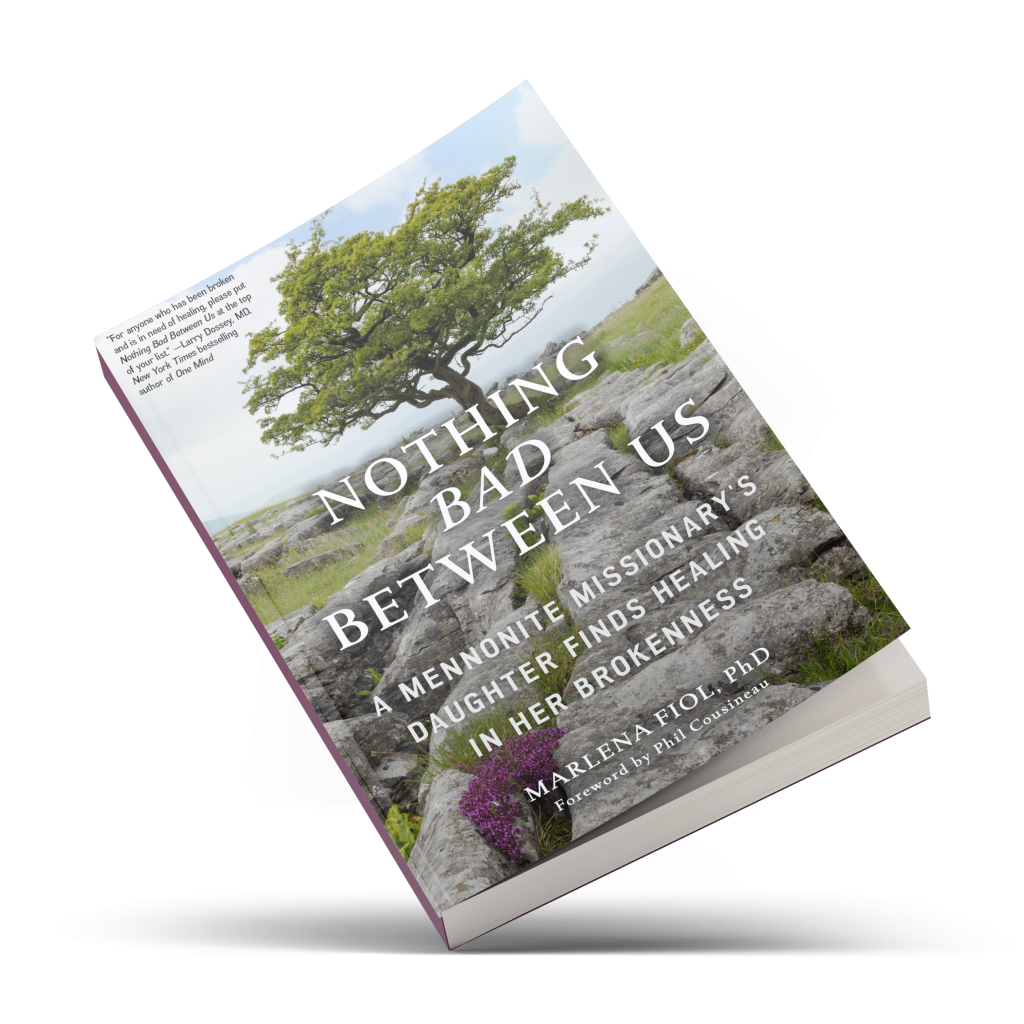

My own personal journey from a rebellious and tortured childhood to eventual healing and reconciliation depended on gradually learning to choose compassion over fear. You can read about it in my new book Nothing Bad Between Us, which is now available for preorder.

Choosing Compassion Over Fear:

Becoming Our Best Selves by Serving Others

featuring Jonathan Reckford, CEO of Habitat for Humanity

As part of our ongoing series, Choosing Compassion Over Fear, I am featuring some of our most cherished friends and colleagues to discover how they have navigated the landscape of doubt, insecurity, tragedy, and fear to move toward becoming their truest selves. Today, we are honored to present a very special excerpt from Habitat for Humanity CEO Jonathan Reckford’s marvelous book, Our Better Angels: Seven Simple Virtues That Will Change Your Life and the World.

The actual act of doing something, of being useful, as my grandmother always used to remind me, amplifies all of the other virtues in this book. My grandmother Millicent Fenwick and my godmother, Jill Ker Conway, were two very important role models for me when it came to having a purpose in life and serving others.

I believe that for both of them a large part of their motivation to serve was a response to hardship and sadness. Both of them could so easily have shrunk away from life because of early setbacks, but instead they turned outward and soared.

Jill was my closest mentor and guide until her passing in 2018. Her complete CV would take up several pages in this book, but here are some of the highlights.

By the age of seven, Jill was doing the same strenuous labor as her two big brothers on the family sheep farm in the extremely isolated wilds of the Australian outback. Her only education was homeschooling from her mother one day a week, but this took a backseat to tending the 32,000- acre ranch. With the onset of a deadly drought, everything fell apart for the family.

When she was ten, her father drowned while trying to fix a water pipe. Her mother tried to keep the farm going, but the drought persisted, and the family was deeply in debt. They moved to Sydney, where she and her brothers experienced profound culture shock. She went to boarding school and finally found the academic environment her eager mind had been craving. After graduating with honors from the University of Sydney and winning the University Medal in History, she applied for a position in the Australian foreign service. She was turned down by the all- male selection committee, while her male classmates were accepted. This was a heartbreak that went on to fuel a life- time of fighting for women’s equality.

Jill earned her PhD from Harvard, where she met the love of her life, John Conway, a Canadian professor of his- tory who had been a mentor to my father. Jill and John married in 1962, the year I was born. Jill began her career as a history professor and then became vice president at the University of Toronto. She became an administrator because when she discovered deep pay inequities for women professors and protested, they put her in charge of fixing it. Jill was the first woman to be president of Smith College, where she doubled their endowment. She advocated for students on financial aid and students who’d had to take time off or cut back their studies because of work and family obligations. She wrote several books, including her bestselling memoir The Road from Coorain.

After her retirement she served on the board of a non- profit focusing on homelessness, particularly among veterans. John was a World War II hero who’d jumped on a grenade to save his company, losing an arm in the process, so veterans’ issues was another cause that was dear to her. In 2013, President Barack Obama presented her with a National Humanities Medal.

Jill had the remarkable gift of presence. I’ll never forget a night when I went to visit her at Smith when I was in junior high. We had a long, wonderful dinner, and even though I was only thirteen years old and she probably had hours of work waiting for her on her desk, she made me feel like I was the center of the world and what I had to say was important. Whenever I had a big life decision, I would always make a pilgrimage to see her and get her advice.

Service was everything to Jill. Despite the losses and disappointments she’d been through, she chose to focus on the blessings. She lived a long, full life, but I still mourn her passing.

Another one of my role models and a person I would never want to disappoint was my grandmother. Grandma had a larger-than-life personality and, like Jill, went through her share of tragedy. When she was five years old, her mother and father were on the Lusitania when it was sunk by a German U-boat. Tragically, her mother died when her lifeboat overturned. He survived by clinging to wreckage, but he went on to marry a difficult woman with whom Grandma never had a good relationship. Her father was a passive presence, deferring to his wife’s wishes.

Grandma was a brilliant person who spoke multiple languages fluently, but she never graduated from high school. She scandalously married a charming divorcé who turned out to be as unreliable as everyone had warned her he was. He decamped for Europe in 1938, leaving her with two young children and his debts, which she was determined to pay off. Without a high school diploma, however, she had a hard time finding a job. She finally got hired as a writer for Vogue and in 1948 wrote Vogue’s Book of Etiquette, which sold a million copies. But it was in her later years that she finally got to live out her ferocious drive for social justice.

She started on the local level, serving on the school board and lobbying for a public swimming pool for her community. She then served in the New Jersey legislature and on the New Jersey Commission on Civil Rights. She earned the nickname “Outhouse Millie” for her efforts to improve sanitation facilities for migrant farm workers. She led the Department of Consumer Affairs for New Jersey and then, at the age of sixty-four, in 1974, was elected to the US Congress. A striking figure at five foot eleven, she wore the same Italian suits she’d been wearing for more than three decades and her signature pearls. Her doctor had told her she had to stop smoking cigarettes, so she got around that by smoking a pipe.

Wayne Hays, the powerful chair of the Ways and Means Committee, once said he was going to withhold pay from her staff “if that woman doesn’t sit down and keep quiet.” She was polite. Her manners were impeccable. But she never backed down.

Her proudest legislative work was an enforcement mechanism for the Helsinki Accords, the first global human rights framework. Walter Cronkite called her the “con- science of Congress,” and it was said she was the model for Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury character Lacey Davenport. She was absolutely tireless. She responded to constituent letters with handwritten letters of her own. She mailed personal checks to the US Treasury after Congress approved a raise for itself that she disagreed with. After her years in office, Ronald Reagan appointed her US representative to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, based in Rome. Where life had sometimes taken from her, she filled it with service and a determination for justice.

The first time I introduced her to the woman who became my wife, Ashley and I were just friends. Grandma was very impressed with Ashley, who had just graduated from law school, and they immediately hit it off. Much later, when we went to see her again and I told her that Ashley and I were engaged, without taking a breath, she took the beloved ring her best friend had given her de- cades before off her finger, the only ring she wore, and gave it to Ashley as an engagement ring. That was very touching to me because I knew that friendship meant a great deal to her and that she was not one to take relationships lightly.

In fact, we got into a conversation that day about love and justice. Yes, the three of us agreed, you needed both. But which was more important? Love or justice? Ashley was making a theological case for love, and my grandmother— which was so rare for her—said, “You know, you’re right.” She didn’t stop there, though. She went on, “But we’ve got to have justice because you can’t always count on love.”

Grandma was right, too, of course, but it made me sad because I knew she had been disappointed by those she’d counted on to love her—her father, her stepmother, her husband—and had been devastated by the loss of her mother and the premature death of her sister, who was her closest friend. She had dedicated her life to justice, perhaps partly as an outlet for her personal grief. She knew from her own life that humans were frail and love was not a sure thing, so there’d better be a legal framework in place operating outside of human emotions. I had great admiration and a little awe for how determined she was to improve conditions for others. I think about how the theologian Frederick Buechner describes vocation: “The place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.” In other words, your calling is a combination of what you want to do and what the world needs.

I’m a little skeptical when we tell everyone, “Go find your passion!” To me, it’s deeper. It’s really about purpose. Passion is a piece of it, but it’s got to be passion plus ability plus a mission that matters. When I think of Grandma and Jill, they exemplify this combination. They didn’t take their calling or their service lightly. In fact, they believed it was part of their spiritual responsibility.

Your calling may not be the same as your job. Whether it is or isn’t, if you can, do some volunteer work. Service doesn’t have to take up a lifetime to become life-changing. Do whatever you can do to be useful, and I’m willing to bet you’ll want to do more.

Service has played a part in all of the stories in this book, but in this chapter in particular I think you’ll see how joyful it can be, and how cathartic and humbling. Above all, service is a way to connect with our fellow human beings. When we connect on the common ground we share doing something useful, we experience true community.

On a practical level, it’s also a great way to forget about yourself for a little while and make new friends. I’ve joked for many years that I want to start a Habitat dating service because I know so many couples who met on a Habitat build site. It’s a great place to meet somebody with a similar worldview and a desire to serve. And that’s a great thing to want in a partner, right?

By serving others, we become our best selves, our better angels.

*****

From OUR BETTER ANGELS: Seven Simple Virtues That Will Change Your Life and the World by Jonathan Reckford. Copyright © 2019 by the author and reprinted with permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

About Jonathan

Jonathan Reckford is the chief executive officer of Habitat for Humanity International and author of Our Better Angels: Seven Simple Virtues That Will Change Your Life and the World. Prior to joining Habitat in 2005, Jonathan served in various leadership positions from Wall Street to a local church in Minnesota. Under his leadership, Habitat has grown from serving 125,000 individuals per year to helping more than 7 million people last year alone build strength, stability and independence through shelter.

Habitat for Humanity began in the 1970s as a grassroots effort on a community farm in southern Georgia. The Christian housing organization has since grown to become a leading global nonprofit working in local communities across all 50 states in the U.S. and in more than 70 countries. Since its founding, Habitat has helped more than 29 million people gain access to new or improved housing.

Find Jonathan on Social Media:

https://www.habitat.org/about/habitat-for-humanity-leadership/ceo (Website)

https://twitter.com/JReckford (Twitter)

https://www.instagram.com/jreckford/ (Instagram)

Jonathan’s Book:

Our Better Angels: Seven Simple Virtues That Will Change Your Life and the World

Choosing Compassion Over Fear

Join Me

If you wish to engage with me in exploring ways we can move toward compassion rather than fear, I invite you to tune in at marlenafiol.com for bi-weekly blog posts and podcast episodes covering a wide range of perspectives, from finding your true calling, to healing estranged family ties. Participants include Jonathan Reckford, CEO of Habitat for Humanity, and Tom DeWolf, Program Manager of Coming to the Table, among many others. The series begins on September 21, 2020 and will run through the first week of December.

Remember, we are together on this journey.

— Marlena