Welcome to Our New Series:

Choosing Compassion Over Fear

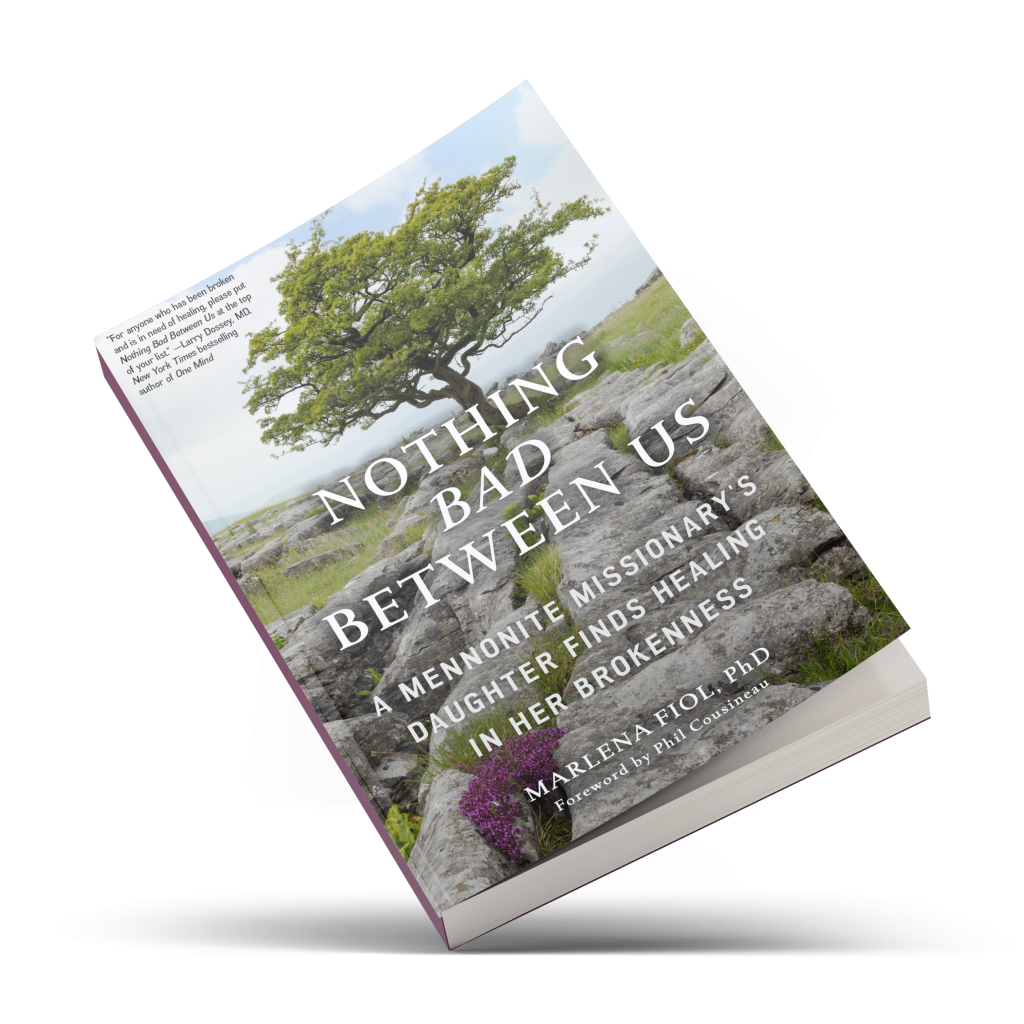

My own personal journey from a rebellious and tortured childhood to eventual healing and reconciliation depended on gradually learning to choose compassion over fear. You can read about it in my new book Nothing Bad Between Us, which is now available for preorder.

Choosing Compassion Over Fear:

Finding Your Passion by Facing Your Deepest Sorrow

My Interview with Shawn Askinosie

Shawn Askinosie

As part of our ongoing series, Choosing Compassion Over Fear, I am featuring some of our most cherished friends and colleagues to discover how they have navigated the landscape of doubt, insecurity, tragedy, and fear to move toward becoming their truest selves.

Today, I’m honored to introduce Shawn Askinosie, coauthor with his daughter, Lawren, of the book, Meaningful Work: A Quest to Do Great Business, Find Your Calling, and Feed Your Soul. Shawn is the founder of Askinosie Chocolate, which was named by Forbes as one of the 25 best small companies in America, and he was named by Oprah as one of 15 guys who are saving the world. Shawn is all about chocolate. I’ve tasted it, in fact, I have the 72% dark chocolate from Tanzania in front of me right now and it is amazing. And no, he didn’t pay me to say that. But he and his chocolate company are also about so much more. Using his company’s revenues, Shawn’s chocolate business has provided over a million meals to hungry students in Tanzania and the Philippines. They’ve delivered thousands of textbooks to schools and they’ve drilled water wells for villagers.

I know you’ll agree after listening to him that Shawn’s life and work inspire each of us to become truer versions of ourselves.

Finding Your Calling

If you like this podcast, please give us a review. Click here for easy instructions.

The following is a taste of my conversation with Shawn.

Q: Can you describe how facing your deepest sorrow allowed you to find your passion?

Shawn: I believe, as Kahlil Gibran said, that we can experience unbelievable transformation and an acceleration of this notion of becoming and connecting to our true self, if we’re willing to explore our own broken hearts and what it is that happened when our hearts were broken.

Q: Do you believe there’s a danger of becoming self-help junkies and never doing the really hard, terrifying work of truly facing our grief and our brokenness?

Shawn: One thousand percent, yes. And it’s called spiritual bypassing, or it could be. There is a danger of addiction to these notions of well-being and self-help and I think that anything that can distract us from becoming who we are and becoming our true self is, in my view, a potential addiction and distraction to the point of danger.

Q: How do you decide which of your values to prioritize when it’s impossible to equally emphasize relationships, quality of the product and service?

Shawn: David Brooks wrote a column in the New York Times a couple of years ago, and he spoke of ordered loves. So, this is what we’re doing. We are ordering our loves in this business.

Q: Too often, the historical missionary model of service has been that the great healer shows up to serve the pitiful, the poor, wounded. What’s wrong with model?

Shawn: I think that it sets up a us and them relationship. It sets up a pattern that can be continued for generations and centuries, if we’re not careful.

When asked if there’s one last thing he’d like our listeners to hear, Shawn says, “It would be that you find someone who needs you right now and serve them. And don’t wait. And don’t wait for it to be the perfect moment. “

About Shawn:

In 2006, Shawn Askinosie left a successful career as a criminal defense lawyer to start a bean-to-bar chocolate factory and never looked back. Askinosie Chocolate is a small batch, award winning chocolate factory located in Springfield, Missouri, sourcing 100% of their beans directly from farmers that they profit share with on three continents. Recently named by Forbes “One of the 25 Best Small Companies in America”, Askinosie Chocolate has also been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, on Bloomberg, MSNBC and numerous other national and international media outlets. Shawn was named by O, The Oprah Magazine “One of 15 Guys Who Are Saving the World.” He has been awarded honorary doctorates from University of Missouri-Columbia and Missouri State University.

Shawn is a Family Brother at Assumption Abbey, a Trappist monastery near Ava, Missouri and the co-founder of Lost & Found, a grief center serving children and families in Southwest Missouri. His new book Meaningful Work: The Quest To Do Great Business, Find Your Calling And Feed Your Soul, co-written with his daughter Lawren Askinosie, is a #1 bestseller on Amazon.

Find Shawn on Social Media:

https://shawnaskinosie.com/ (Website)

http://www.askinosie.com/ (Website)

https://www.linkedin.com/in/shawn-askinosie-6991595/ (LinkedIn)

Shawn’s Book:

Meaningful Work: A Quest to Do Great Business, Find Your Calling, and Feed Your Soul

Books Mentioned in the Interview:

Nothing Bad Between Us: A Missionary’s Daughter Finds Healing in Her Brokenness, by Marlena Fiol, which is now available for pre-order on Amazon.

Falling Upward: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life, by Fr. Richard Rohr.

About Marlena Fiol:

Marlena Fiol, PhD, is a globally recognized author, scholar and speaker. She is a spiritual seeker whose work explores the depths of who we are and what’s possible in our lives. Her significant body of publications on the topic, coupled with her own raw identity-changing experiences, makes her uniquely qualified to write about personal transformational change. She is also a certified tai chi instructor and freelance writer whose most recent work has appeared in numerous literary magazines and newsletters.

Find Marlena Fiol on Social Media:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

LinkedIn

Podcast Transcript:

Shawn, welcome. It’s so good to have you on the show.

Shawn: Oh, thank you. Boy, that was quite an introduction. I was listening to that, thinking, “I better not say anything. Just leave it at that.”

Marlena: Shawn, for two decades, you were a hard-charging type A criminal defense attorney. You write in your book, “I loved my work until I didn’t.” You hit a roadblock in 1999, and there seems to have been a pivotal moment when you knew that you no longer loved what you were doing. Would you tell our listeners a bit about this and how it happened?

Shawn: Sure. I specialized in the defense of murder cases and most everything I handled was a serious felony of some kind. And in this moment that you’re speaking of, it was at the conclusion of a first-degree murder trial, and I was quite emotional. The jury had been sequestered, a lot of high-profile attention to the case, especially here in Missouri and some national. And it was a case involving the defense of not guilty by reason of insanity, the insanity defense, which never works even if it’s true because juries just don’t want to use it. So anyway, very, very emotional. At the end of the trial, the judge called us into chambers and he and I had fought the whole way through the trial and he threatened to hold me in contempt, put me in jail.

And I was about ready to give the closing argument, and the judge called us in the chambers and he said, “Well, Shawn, here’s what we’re going to do. We are going to have the prosecutor,” and the prosecutor was in chambers too, “We’re gonna have the prosecutor lower the charge to second-degree murder. I’m going to put your client on probation and that’s that.” Now, remember this is first-degree murder, and the possibility was life without parole and not the death penalty. And so there was quite a change of events. And I went out to tell my client, this woman charged in a very, very tragic case, and I believed in her and it was a really emotional meeting and just in this small anteroom off the courtroom. And I said, “You know, we can take this further. I have my closing argument ready and we’ll see what the jury will do. And maybe we’ll, you know, this or that.” And she said, “No, Shawn, you’ve done a good job, it’s over.” And she basically comforted me because I started to cry at that point and I knew at that moment when my client comforted me, that it was time to go.

Marlena: Beautiful moment. Around that time, I think it was, that you began volunteering in a palliative care department of a hospital, and you write that this service work allowed you the space, I think you called it a bridge. It allowed you the space to find clarity about your true passion. What was it about the service work that gave you that clarity?

Shawn: During this time, so right after that moment that I just described in the courtroom, I knew I had to do something else and it began to sort of manifest in my body, you know, my chest was hurting and things like that and little panic attacks. But I didn’t have some kind of big, huge savings account to fall back on. I had to keep trying cases and practicing law. And during this, what turned out to be a five-year period of looking for the next thing, I was researching, and reading books, and talking to people, and coming up with franchise ideas, and nothing was really reaching a place within me that I would call a place of inspiration. And I was very troubled by that, which made the problem that much worse. And I started to have some anxiety and depression and I thought, you know, “Gosh, as a lawyer, I was so successful. Why can’t I figure this out? Why can’t I just read the right book?”

And so during that time, I started volunteering at Mercy Hospital in their Palliative Care Department because when I was 14, my dad died of cancer. He was a lawyer too, and it was just terrible, just a really tough situation. And I was with him when he died, and the church that we were going to at the time really handled it poorly, and that’s a whole other story. But anyway, so I started meeting with the patients. They would give me a list of patients to see in various departments in the hospital, so oncology, neurology, cardiology, wherever, they were all in some state of dying. It’s kind of like hospice in the hospital. And I was there just to knock on their door and say hello and just visit. That’s it. Just whatever they want to talk about, pie recipes, fishing, whatever. And I always concluded by asking them if they would like me to say a prayer for them before I leave, and almost all of them did.

And then where the experience deepened is when I asked them what they wanted me to pray for. And this then went to the center of my own brokenheartedness that I’d experienced with my father 25 years before that. And so this is a very long way of answering your question, and that is the service in that moment, in that hospital, was directly connected to my own broken heart, and therefore, you know, when I would repeat the patient’s words back to them, what they wanted me to pray, I didn’t judge it. I just…whatever they said, if they prayed for healing, I prayed for healing. If they prayed for death, I prayed for death. And if they prayed for the comfort of their family or any…just using their exact words. And there were times when I would leave my work at the hospital on days, not every day, but some days, and it was almost like when I was walking to my car, that I was levitating three or four feet off the ground walking to my car.

And what that experience was, it was a complete joy in a way that I’d never known it before. And so, in that time of joy, there was a space created that was an emotional space, a space of consciousness that was not available to me by reading a book or researching the way I had as a lawyer. And it was during that time of space that I thought, “Hey, maybe I should make chocolate from scratch.” Not at the hospital, not while I was at the hospital, but just, you know, just during those five years. So that’s how it happened.

Marlena: Did you know at the time that your service work would do this for you? Or is this a sort of retrospective sense-making?

Shawn: I did not know that it would do it for me. I did not. And that’s part of this paradox. And so to your listeners, I would say, because they’re thinking what you just asked and they’re thinking, “Oh, hey, I understand this. Are you saying that if I need to connect with my true self, if I need to engage the process of becoming,” to use the words you used in the introduction, “does that mean, I just…can I just go serve some people and kind of that’s it, I’m done?” No, you cannot. And that’s the paradox. Gandhi said, “If you want to find yourself, lose yourself in the service of others.” So this is the mystery. This is the paradox, it’s counterintuitive, but you’re not expecting, when doing this, you’re not expecting that there will be answers written in the sky for you or some loud audible voice, and… That’s not it. That’s not it. And we also don’t know the timing. We don’t really necessarily understand the timing of the clarity that we receive in our lives. We don’t understand the context necessarily, but what this process allows is an opening. It allows an opening for us. And so that’s where we live.

Marlena: Yeah. In a similar vein, you’ve written that doing a whole bunch of research is probably not the best way to find your passion. I think you said it can often lead to paralysis. And it’s also not as simple as just saying, “Follow your dream.” That’s nice, but not terribly helpful. When you write about finding the sweet spot for your life and your work, you draw on Jim Collins’ Hedgehog Concept, which he developed in his book, “Good to Great,” the sweet spot being that intersection of your passion, what you do best, and what the world needs. Of those three, Shawn, would you say there’s one that’s more challenging than the others to identify?

Shawn: I think it really depends on the person, but what I’ve been finding in talking with groups about these issues now for many years is that…and I don’t think this necessarily applies to any particular age of the person either, but what I’m finding is that people are having a challenge identifying their passion. And I think that if I would have… My grandfather, he was a simple farmer, not highly educated, my grandparents, both of them, you know, who are now my heroes, although they’ve been gone for 25 years, but, if I could have this conversation with my grandpa and say, “You know, I just don’t think law is my passion anymore and I can’t find my new passion,” he would look at me with a blank stare and not have a clue what I’m talking about.

And so, I think that this notion is somewhat new, but I also think that the challenge in connecting to it is particularly new, and also, I think it’s insidious in our culture. I think that because of the amount of information that’s available to us online, which is endless, that it’s created a culture in which we…well, to use your words, I mean, it makes it even more challenging, I think, to become our and connect to our true selves. And so that’s what I find, is that people are having a real trouble not identifying their talents, not identifying what the “world needs,” however we define that, but it’s, “What do I want to do? Where do I want to…you know, how do I want to live out the 80,000 or 90,000 hours of my life at work? If I live that long, what do I want to do?” That’s, I mean, I find people very, very challenged by that.

Marlena: Yeah. You spoke of the broken heart that you faced when you sat with patients at the hospital, heart broken from your father dying when you were 14. And in the book, you quote Kahlil Gibran as saying, “Our greatest joy is sorrow unmasked.” In my new book, “Nothing Bad Between Us,” I describe my healing journey as beginning from a place of complete brokenness. And your exploration of your deepest sorrow allowed you to uncover a passion you didn’t even know you had. I think to some of our listeners, these may sound like oxymorons. Can you describe how facing your deepest sorrow allowed you to find your passion?

Shawn: Anybody listening, so we’re going to assume we’re not talking about middle school kids, although they totally get this. But…

Marlena: Maybe better than some of us.

Shawn: Although your grandsons…but then again, maybe your grandsons, I’m not sure exactly how old they are, but maybe they’re listening. The thing is, if we live very many years, we experience brokenheartedness. And when I talk to professionals, young professionals, or even middle-aged professionals, or ones my age, you know, I do run across people who say, “I don’t know that I really have experienced a sorrow or a real broken heart.” I remember specifically one of my friends saying this to me, and I said, “Well, what about your divorce? What about your inability to see your kids for a period of time? What about this?” And he was like, “Oh, yeah, yeah, maybe that.”

So what I first ask of people, and then let me also just kind of parenthetically note that this topic right now that you and I are talking about is not necessarily for everyone. I think that this is a special lane, it’s a certain subset of an audience that connects with this, who, when I say the word or words broken heart, brokenheartedness, sorrow, people will either understand that or not. And to those people who don’t understand it, I say, please, let’s talk about a new life for you in which we can break your heart because you’re living half a life. If you’re not open enough to let your heart be broken so that you can experience what that means, because grief and love are our sisters, and we can’t know the depths of love if we’re not able to embrace grief and brokenheartedness and sadness.

And so, I believe, as Kahlil Gibran said, that we can experience unbelievable transformation and an acceleration of this notion of becoming and connecting to our true self, if we’re willing to explore our own broken hearts and what it is that happened when our hearts were broken. And are we willing to have a conversation about that? Can we talk about it with a trusted friend, or a professional, or even ourselves, or a family member? And then, can we serve someone that we know who might need us out of that place in our own broken heart? That is the core of what I’m talking about. That is… Because if we go through this exercise of, “Hey, let’s identify your talents, your passion, and what the world needs,” and there’s going to be some overlap there.

There’s going to be some intersections, and, “Hey, there’s your job. It just came to you, go for it.” That’s okay. You can do that. And I talk to people who do that all the time, and they love that exercise. But my belief is that they’ll probably be back again in a few years wanting to find another shiny object in the periphery to start over, you know, to find a new job, to find something else to fill them because our true selves are waiting. They’re waiting for us. And the pathway, I believe, and one of the most beautiful portals to the experience of connecting with our true self is through our own brokenheartedness and the grief in our lives.

Marlena: I love that, that our true self is waiting for us. It seems to me that right now, we’re at a moment in history when self-help materials are everywhere, and finding yourself is the thing to do with workshops, classes, I don’t know, books, podcasts, seminars. So here’s my question. Do you believe there’s a danger of becoming self-help junkies and never doing the really hard, terrifying work of truly facing our grief and our brokenness?

Shawn: One thousand percent, yes. And it’s called spiritual bypassing, or it could be… Well, I think there is a danger of addiction to these notions of well-being and self-help and I think that anything that can distract us from becoming who we are and becoming our true self is, in my view, a potential addiction and distraction to the point of danger. And the really treacherous thing about this is that it looks good. In other words, we would say to ourselves, “Well, of course, why wouldn’t I read my 10th Wayne Dyer book? Why not? I mean, that’s how I’m going to find myself.” And, of course, it appears to be a very laudable effort, but you’re right. We need to put the Wayne Dyer book down and do the work. We need to do the work. You know, I read a lot of books on prayer and contemplative prayer, and meditation, and spirituality, but it doesn’t make me a better meditator. It’s just interesting for me to read about, and I love reading about Thomas Merton and I love reading these things. I love it, but I also recognize that it’s not necessarily gonna make me better at the contemplative practice itself. I have to do it.

Marlena: Yeah. So you discovered your own personal vocation. How did you then move from a personal to a business vocation?

Shawn: The way that this happened is, and I think that many entrepreneurs can relate to this. And that is, that if you have begun the process of awakening and you’re on that path, circuitous though it may be, that when the business idea comes to you and you start writing your business vision and your strategic plan and your business plan, that, invariably, your personal vocation will be woven into the fabric of those notions and how you’re going to proceed step by step in your business. I think that if you really truly are beginning to connect with your true self, that it’s almost impossible for those things to, you know, be held back in your business. You can’t hold them back because they’re part of who you are. They’re not separable. And I say this a lot that, you know, I could give the cocoa beans, you mentioned the 72% Tanzania, in fact, I was, literally, one hour before we started talking, I was speaking with our field rep in Tanzania about those cocoa beans.

And I could give those same cocoa beans to somebody down the street, I could give them the recipe, it’s easy, sugar and cocoa beans, and give them my equipment and say, “Okay, go make the chocolate bar.” It would not be the same chocolate bar. And I’m not saying that in some sort of new age, woo-woo kind of way. I’m saying that who I am as a person and the people in our company, that collective is inseparable from the product that we make. You can’t separate them. And that’s what I love about this idea of business and life just kind of being all, you know, macro-made together, and I think it’s one of the beautiful things about it, you know, because it’s kinda messy, it’s not perfect, it’s wabi-sabi as they say, and so we say, “It’s not about the chocolate. It’s about the chocolate.”

Marlena: Yeah. I love that.

Shawn: And that’s a very non-dual, you know, sense of it’s not about chocolate, it’s about these things that you mentioned in the intro, it’s about the children that we’re feeding, who are severely malnourished, it’s about afterschool programs for kids in the village, it’s about a preschool that we just built in Tanzania for 300 kids that, unfortunately, is closed right now due to the pandemic. But that’s not about chocolate. It’s about relationships. It’s about people. It’s about connecting one true self to another true self. That’s what it’s about. But on the other hand, it’s everything about chocolate. It’s about making the best tasting chocolate that we possibly can and laser focusing on that and nothing else so that it’s beautiful, as beautiful as we can make it. And so that’s how I believe these things sort of run into each other and how, when one begins to awaken, you’re on the right path. You go start a business and be true to yourself.

I heard James Finley mention this week on a podcast, and he was one of Thomas Merton’s novices, and he’s with Father Richard Rohr, and he said, I love this, he said, “I will not break faith with my awakened heart.” And what I love about that is it speaks to me because, especially in this time that we are in, you know, sometimes we have challenges and we think to ourselves, you know, “Why is this happening?” or “Why am I facing this struggle right now?” And for those who are on the path of reawakening, I can hold dear to what he said, which is, “I may not feel like it now, but I’m not going to break faith with my awakened heart.” And that’s what we do in business when we face troubles like right now, like lower sales, and, you know, are we going to have to let people go? And will the business itself survive? Maybe it’ll end. But I’m not going to break faith. I’m not going to break faith.

Marlena: Yeah. I just want to let our listeners know that this interview is taking place mid-May. It won’t be published for a bit, and so I just wanted to orient the listeners to the moment in time that we’re talking about. So allow me to read your vocation statement for our listeners, “We at Askinosie Chocolate exist to craft exceptional chocolate while serving our farmers, our customers, our neighborhood, and one another.” And here’s the part I love best, “Striving in all we do to leave whatever part of the world we touch better for the encounter.” And Shawn, you also write that your business vocation is about prioritizing. It’s prioritizing relationships, the quality of the chocolate, the service. My question is this, how do you decide which of those to prioritize when it’s impossible to equally emphasize relationships, quality of the product, service?

Shawn: We attempt to give ourselves some grace on the idea of balance. So we don’t do this in a scientific way. We do it by harmonizing those priorities. And that means that we can be very flexible in meeting a particular need at a certain time and we can… David Brooks wrote a column in the “New York Times” a couple of years ago, and he spoke of ordered loves. So this is what we’re doing. We are ordering our loves in this business. And that is the way that we would do this in our personal lives, when we order loves with, you know, our children, and our grandchildren, and our friends, and our spouse, it’s not a perfect balance. It’s one where we’re here, we’re present in this moment. And is there a need? Am I drawn to answer the question in some way that might be different than I would answer it, you know, two weeks from now?

And I can give you an example, and that is literally two hours ago, so I was talking with our Tanzanian field rep, and she’s a graduate of the University of Dar Es Salaam and she lives in the village and works there with farmers for us and with the kids. And we were talking about the price of cocoa beans and we’re in the middle of negotiating a contract for this year, which is a really challenging thing to do given what’s happening. And so she said to me, she said, “Are you in a position to pay more for the cocoa beans this year? Can you pay more? And would you consider that?” Well, that’s like the opposite question that people… I mean, right now people are just saying, “Can I even just get an order?” You know, I mean, but they have a need, and it’s very complicated as it relates to government regulation and everything, but we’re probably going to pay more. And you might be thinking, “Well, gee, isn’t that going to hurt your business? Isn’t it going to impact…?”

Well, I don’t think so. I don’t think so. And most of these complex decisions, the best way I can tell you is, and this is really not much of an answer, but they flow. So I have such confidence that we will… I can’t even… I have such confidence that I won’t make the wrong decision in collaboration with the other leaders here at my little company, my daughter, Lawren, that you spoke of, who is my coauthor, and the farmers. It’s, you could say, faith, that we’ll make the right decision at the right time. And it’s hard, but those aren’t the things that keep me awake at night because I just know, I know that it’ll be okay one way or another. And if my decision is one in which my heart is in the right place, truly, then it’ll be okay. Even if some financial calamity happens, it’ll work out. It’ll be okay.

Marlena: That’s quite an inspiration for our listeners. Shawn, I love a question that you ask in your book. How much is enough? How big is big enough? As I’m sure you know, the leading cause of small business failure is overexpansion, and it often happens when owners refuse to see the difference between success and expansion of the business. You’ve stayed intentionally small and you operate from cash flow. Why and how did you make the decision to do this?

Shawn: This is a great segue because it has to do with the question that you asked me about priorities and what I said was ordered loves. I call it reverse scale in the book, and as you mentioned, you know, many businesses fail because they’re growing too fast. They have come under the spell of our culture, which says, “If you don’t scale, then you are of no value,” you know, your company is not valuable or your idea isn’t valuable if it’s not scalable and scalable quickly. And so what I’ve tried to do is push against that notion and intentionally stay small. Like you said, we have 16 full-time people, and that has cost us some things. I mean, we’ve had to turn down business, and people have said, “Well, what if we make your Chocolate University Program bigger? What if we feed more kids?” And of course, that’s very tempting, but here’s why.

It’s because when we have ordered loves in the way that we have in this business, it has permitted me to roll up my sleeves and take kids to Tanzania. It has permitted me to… My next origin trip will be my 45th origin trip since I started the company. I go every year to visit the farmers. And I am not tired of doing that. And why? It’s because of the human connection, it’s relationships, it’s people, it’s being able to see our students, and, you know as a professor what it’s like to see a student who gets it and who is transformed even by a short-term experience.

Marlena: Yeah.

Shawn: And I would say, let’s take it even a little deeper. There are some experiences in my business in which I have encountered the divine, and I know it when it’s happening now, I see it, I experience the thin veil being lifted between here and there, and it is a moment, not very long, but it’s a moment of near-complete connection to my true self and union with the divine. And then it goes away, but I can reflect on it and I know what happened and when it happened and I treasure those moments. And one of my fears is that if I was busy finding investors and trying to get partners and more business and, you know, just growing, growing, growing, that I would miss that chance and that I would, before you know it, just be busy managing and supervising and writing checks and not being shoulder to shoulder with people in mutuality and kinship. I’d rather do that and not have as much money and be connected in those moments than have a jet, or whatever. Although, you know, some days a jet would be nice.

Marlena: This is a great example of ordering your loves. So, in the introduction, I mentioned that the theme of this podcast season is “Service in Our World Today.” In my book, “Nothing Bad Between Us,” I describe my parents’ deep devotion to service. They were Mennonite medical missionaries in Paraguay, and among many other contributions, they changed how leprosy is treated on the planet today. So their passion for service made a huge difference in the world. But it also took a toll on our family life and it turns out this is not at all uncommon. So would you share with us what you’ve learned about balancing your personal life and your passion for service?

Shawn: My spiritual director at the monastery, which we haven’t spoken of, but I have been connected to a Trappist Monastery in Southern Missouri, in the wilderness, in the Mark Twain National Forest for almost 20 years. And in the last, seven years ago, I became a family brother there and recently took my life promise. And I’m not a monk, but I live with the monks when I’m there behind the cloister, and my spiritual director of 20 years is now 90, and he’s been a monk since 1952, praying the psalms every day. And a couple of years ago, we had the opportunity to start another school lunch program in the Philippines where we’re funding and managing school lunches for all the kids in the school. And he’s a very humble, very soft-spoken man, but he encouraged me to not do that, to not do that. And it really took me by surprise, because I didn’t understand why, if I had the opportunity to feed children, why would I not start another program? And he explained to me that I personally needed the rest, and that I needed, in order to be my best self, and not in a selfish way, but in a way to live out my faith, that I would say no to that.

And it took me time to understand this, but he was trying to teach me not that it’s a bad thing to feed kids who are hungry, of course, anybody would say that’s a good thing. But it can take its toll to the point that my own life as a husband and father and brother and friend would be compromised. And so he taught me, not in a mean way, that God doesn’t need me. He taught me that God does not love me any more because I feed more children. That I am feeding the children because God loves me, not so that he will. And this is a very difficult concept for super motivated, ambitious people, even in doing good work to understand, especially when we’re doing good work. In fact, I even believe if we can go to this place, and maybe it’s not appropriate, but I actually think that the temptation to overdo it in good works is the work of a dark force. That it’s a potentially…I’m not going to go as far as to say evil, but I’m going to say that it’s dark, because it’s a trick. And the reason it’s a trick is because the temptation to do it is our own voice. So the darkness is whispering in our own voice, in our ears, and so that’s pretty convincing. That’s very persuasive. That’s very, very persuasive.

Marlena: No, I’m very, very happy that you went there. And I would add that it’s the voice of our ego often that is whispering to us to do that.

Shawn: Yeah. Yes.

Marlena: Yeah, no, thank you for that. I’d like to touch on the important relationship that you also write about between those being served and the servers. I think, too often, the historical missionary model, if you will, of service has been that the great healer shows up to serve the pitiful, the poor, wounded. By contrast, when you take your superstar students from Missouri to Tanzania, you tell them, “Your job is not to help. It’s to receive, to learn from them, to let your heart be transformed.” Shawn, what’s wrong with the old missionary model I described?

Shawn: Well, I think that it sets up a us and them relationship. It sets up a pattern that can be continued for generations and centuries, if we’re not careful, that we are the great servers and they are the recipients of the service. We are the healer, they are the healed. And I think that many spiritual teachers across many faith traditions would say that compassion is from a place of mutuality. As I was saying earlier, it’s a place of shoulder to shoulder connection, where we allow ourselves to experience role reversal from what our expectation might have been even for a novice, you know, experiencing these things that I’m talking about. It’s where the teacher becomes the student. It’s where the healer becomes the healed. And I think Father Greg Boyle writes about this really well in a book that I quoted in my book called “Tattoos on The Heart.”

And he’s a Jesuit priest who’s worked among gang members in Los Angeles for 30 years. And I think he really does a great job of talking about this idea of mutuality. And that is a notion, I think, that… And I’m not going to generalize and say it was across all, you know, missionary traditions, or that all missionaries were not operating within a space of mutuality, but I think that when we can come alongside a friend, and be there, not above or below, but equal to them as friends and partners and people that we love, then that’s the place of transformation. That’s the place of miracle. That’s the place where God dwells. And again, in fact, Father Greg Boyle would take it even further and he says, “Do you want to find God? Do you want to see where he’s working? Go to the low places. That’s where. Go to the low places.”

And so, for missionaries, they were often in the low places, but they were there, I think, in many instances, as I was saying earlier, the sort of expected traditional roles of healer and healed and provider and service recipient. And I think it eliminates…it doesn’t eliminate, it diminishes the opportunities for expansive amounts of compassion and miracle. In fact, I believe from what I’ve experienced in Africa, among the agricultural or rural people, I think that in the next century, if the African people that I’ve experienced are able to maintain their own culture and traditions, that they will become missionaries to us, that they will become missionaries to us in the United States and they will teach us how to worship and how to have joy and how to live and… I do predict that.

Marlena: I just want to reiterate what you also said, Shawn, and that is that neither one of us is saying that all missionaries have approached the work in this dualistic way. But it has been a model historically and it’s a very important message. I think that the real service happens when we are in community with and collaborating with those whom we are serving. And in some ways, they are serving us as well. What would you say are some of the things you’ve learned from those you serve?

Shawn: Well, the first thing I’ve learned is that they’re serving me. I was having a conversation in a house with one of the elders in the community in the little village there in Tanzania, and his name is Mr. Livingston and his wife, Mama Mpoki, is the one that you see on the front of that chocolate bar that you have. And she is the chairwoman of the cooperative with 60 farmers, not him, her. And it’s a matrilineal culture there, and then the Kisa tribe that she’s is a member of. But we were in their house, and they wanted me to explain what nursing homes were and they didn’t understand why we would have such things. And we were talking about it and they very seriously told me, they said, “When your time comes to go to a place like that, we want you to move here. We want you to live among us, and we’ll take care of you.”

Marlena: That’s great.

Shawn: And I mean, I get emotional now even just repeating that story, because they mean it. They mean it. So that’s what I’ve learned. I’ve learned things like that.

Marlena: Yeah. So you talked to us earlier about your spiritual director, and one of the things you write about in your book is that you had or perhaps still have personal struggles around doing versus being and that your spiritual director talked to you about learning to just be. And you write, and I quote, “I only wish someone had suggested this to me in my 20s.” Here’s my question. Do you think really you would have heard the message in your 20s?

Shawn: No.

Marlena: Yeah. Yeah.

Shawn: No, no, no. Well, I think maybe I should have better articulated my wish that, just to say what you said, I wish I would have been able to hear such a message in my 20s. And I understand why I didn’t and why many don’t. Although I think that’s changing a little bit. I’m just continually amazed by the young people that I work with and how aware they are compared to, say, young people 15 years ago. But yeah, I wish that I could have been a person then open enough to hear that message about being versus doing, but it’s okay.

Marlena: Yeah. We talked earlier about James Finley and Father Richard Rohr. Father Rohr is a very important spiritual teacher for me, and one of the things he wrote about in his book, “Falling Upward,” is that in the first half of life, we must build the container. We must do before we can fully be in the second half of life. We need to do the stuff of being a success according to the world standards in order to then fall upward in the second half of life to be. And so I think that that’s very relevant to what we’re talking about.

Shawn: I agree 100%. I love that book and I read his newsletter every day. And, like you, he’s an important teacher for me, as James Finley is as well. And yeah, this is our path, and that’s why I think, yeah, it’s okay. It’s okay because I would not be where I am, but for the time of building during those years.

Marlena: Yes. You write that becoming our true self is like grabbing fog. I love that metaphor and the mystery in that metaphor. But you also say that momentary glimpses affirm us at the very core. Do you believe the process of becoming our true self is really ever finished?

Shawn: I think it’s finished at death. At the moment of death, we will experience the complete union of our true self with the divine, and I don’t think that we can ever fully, fully become our true selves without that. And it’s why the monastic tradition of dying daily, it’s not just words. And so, the compline service at 7:40 every night at my monastery concludes with the abbot saying that and asking for a restful night and a peaceful death. And they mean it. And so I think this notion of true self is absolutely connected with our death and preparing for our death. And that’s why I say we can have these momentary connections and we can have a life where our practice will lead us to them more frequently, and also in unexpected places. But I think for it to be complete, we… And, you know, Eckhart Tolle talks about this a lot, Michael Singer talks about this a lot, and I think this aspirational notion of the eternal now is absolutely a real possibility, but it’s not permanent until we die, I think.

Marlena: Shawn, if there were one last thing you’d like our listeners to hear, what would it be?

Shawn: It would be that you find someone who needs you right now and serve them. And don’t wait. And don’t wait for it to be the perfect moment. And don’t wait for the perfect thing to say and to pray that a person is put in your path who needs you because they’re out there. And that’s what I hope people will take away.

Marlena: What a lovely challenge. This has been such a meaningful conversation, Shawn. Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me.

Shawn: Well, thank you. Gosh, it’s been an honor and I’ve loved that we’ve been able to talk about all the people that we both love, and, oh, there’s my prayer bell right now. Well, that’s perfect timing. Those go off five times a day. So thank you.

Choosing Compassion Over Fear

Join Me

If you wish to engage with me in exploring ways we can move toward compassion rather than fear, I invite you to tune in at marlenafiol.com for bi-weekly blog posts and podcast episodes covering a wide range of perspectives, from finding your true calling, to healing estranged family ties. Participants include Jonathan Reckford, CEO of Habitat for Humanity, and Tom DeWolf, Program Manager of Coming to the Table, among many others. The series begins on September 21, 2020 and will run through the first week of December.

Remember, we are together on this journey.

— Marlena