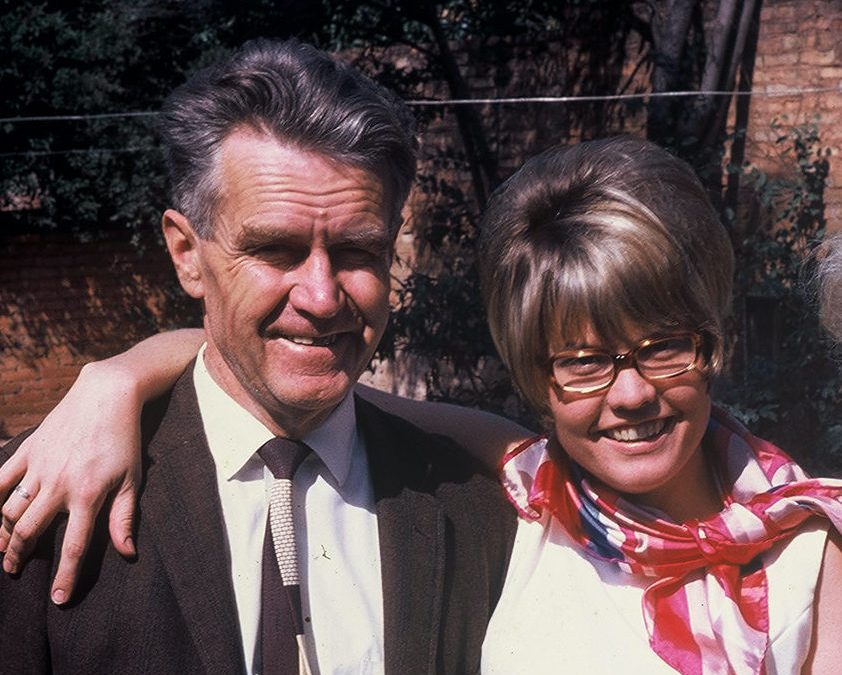

My Dad and I (1970)

In honor of Forgiveness Day, which is observed on June 26 this year, my YouTube show this week is about my journey of forgiveness with my father and his Mennonite clan.

My father and I hurt one another. Deeply. He was an angry disciplinarian. I was a horribly rebellious child. You can imagine the rest. I can assure you: It was not pretty.

Fortunately, we found mutual forgiveness several decades before he died – for ourselves and for each other. “Doa ess nuscht tweschen ons – there is nothing bad between us,” we said to one another in our native Low German at every farewell.

My father and I were able to release feelings of resentment toward each other, which is how psychologists generally define forgiveness. This was a big deal for me. Which is why I wrote a book about our journey to reconciliation, Nothing Bad Between Us, which was released by Mango Publishing in 2020.

Throughout my life, I’ve often found it challenging to forgive others, especially those who don’t even recognize or acknowledge having hurt me. As a result, when I’ve done the hard work of releasing my anger and allowing forgiveness in those situations, I have considered it a major accomplishment.

So, I was surprised when one of my podcast guests, Phil Cousineau, suggested that forgiveness is not enough. Consistent with his powerful and thought-provoking book, Beyond Forgiveness, Phil argues that forgiveness is only the first step. It’s kind of going halfway and then stopping, and does not go anywhere close to creating a deep, long-lasting reconciliation.

What is required beyond forgiveness?

Atonement, Phil says. He quotes Arun Gandhi, grandson of Mahatma Gandhi as saying, “If there isn’t the second step [atonement], then the peace that we have forged in our love life, at work, or in nation-building, will dissipate like the morning dew.”

This word ‘atonement’ immediately reminds me of Biblical accounts from my religious childhood. But it turns out to be not all that religious, from Phil’s point of view. He said, “Atonement is an act that rights a wrong, makes amends, repairs harm, offers restitution, attempts compensation, clears the conscience of the offender and relieves anger for the victim.”

And then, being the wordsmith that he is, Phil says: “The word atonement means ‘at-one-ment,’ being at one with somebody.”

So, I ask myself: Did my dad and I ever right the wrongs, make amends, repair the harm, offer restitution, or attempt compensation? It seems clear to me that we did not. In fact, my father and I never even sat down to explicitly talk about the abuse and the hurt. We never openly acknowledged that any of it happened.

But over the years, we observed serious cracks in each other’s armors, as each of our lives crumbled, and we learned to be more vulnerably present with one another. I wonder if at-one-ment can happen in complete silence and with no explicit acts of making amends, when the offenders and victims – and my father and I were assuredly both of these – vulnerably acknowledge each other’s mutual brokenness? It seems to me that our acceptance of each other with all of our warts was such a relief that we never looked back.

I believe Phil might agree with my conclusion. When I asked him what form of closure we seek as human beings when someone has been wronged, he said without a moment’s hesitation: Wholeness.

The wholeness that comes from knowing that we are one with all our beautiful cracks and imperfections.