At the MCC library in Akron, PA

This week I met my parents — for the third time. Like most of you, I met them for the first time as a child, and then as we grew older together. I came to know them for the second time in the years following their deaths. My parents wrote prolifically about their lives in diaries, memoirs and in what they called Personal Glimpses, which they sent out to hundreds of people.

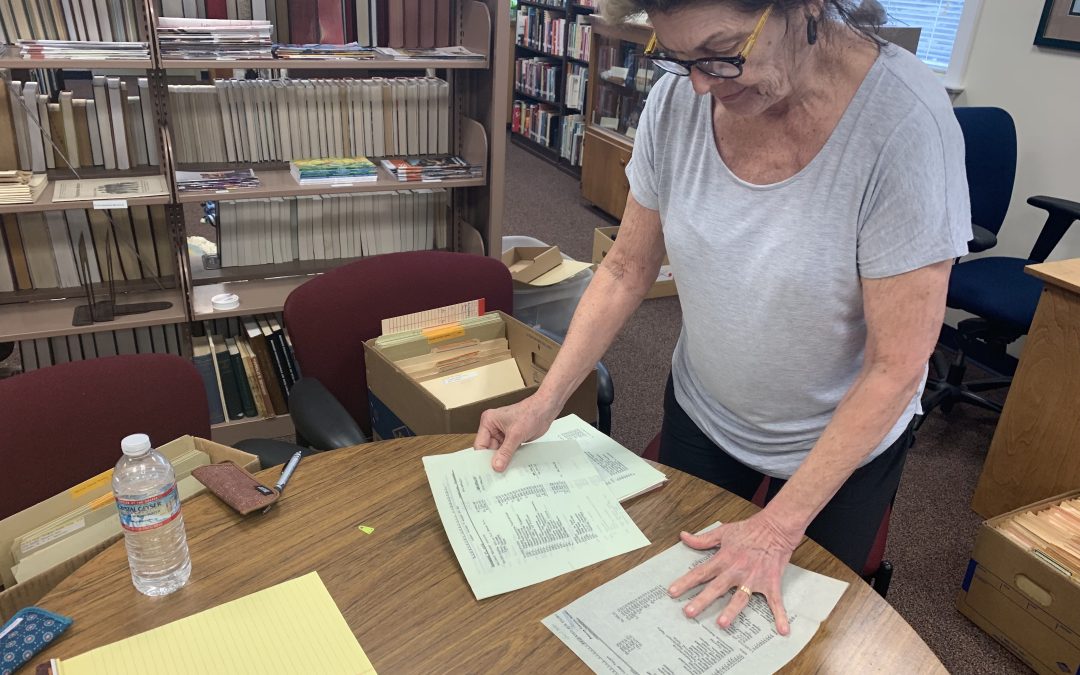

I met them for the third time this week in Akron, Pennsylvania, at the library of the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) headquarters. My husband Ed and I are writing an historical novel about their lives. We spent three intense days sorting through and photographing a large collection of professional papers written by them, to them and about them.

MCC sponsored my parents as medical missionaries in Paraguay, South America. In their thirties, they devoted themselves to caring for people in the remote, nearly uninhabitable Gran Chaco of western Paraguay. In the decades that followed, they founded and ran a leprosy station hundreds of kilometers to the east. They were acknowledged by then president of the American Leprosy Mission, O. W. Hasselblad, as the people who carried out the courageous and pioneering work that serves as the basis for the way leprosy is treated in the world today.

My parents were humble people. They never bragged about their work. I grew up on the leprosy station knowing that what they were doing was important; it was God’s work that always came first. What I didn’t know until last week in the Akron library was how genuinely difficult life was for them.

They pushed the edges of the envelope year after year after year. They went where most people would fear to tread. They strove to change the way things were done in each of the worlds they entered. And the people around them who believed in the old ways and didn’t see the need for change pushed back. Hard. For example, the government of Paraguay threatened them with jail, the American Leprosy Mission and the Mennonite Central Committee pushed back by cutting their funding, and neighbors surrounding the leprosy station came out with a truck full of rocks to destroy their buildings and kill them if necessary. And yet they continued forward, believing that they were guided by a higher power to care for those in need.

I knew they had led a challenging life. But I had no idea how hard the years had been for them. Over and over again, the documents we found in the library reveal how my parents were consistently badgered by others, and how they courageously badgered back in return. It was an ongoing war. But they never complained, so I didn’t know.

As Ed and I dug into the decades of official documents last week, I saw my parents newly. I felt sadness. I felt compassion. And I felt a deep desire to know them better. But they have long ago left this planet. As an adult, I should have realized that life was often difficult for them. But like many of you, I was busy. And probably self-centered. I failed to ask the questions that I wish I could pose to them today.

Why am I interested? Why do I write about my parents? The easy answer is that they were great people and I wish to share their story with the world. And like many of you, I want to preserve my family’s history.

All true. But I’m probably more selfish than that, consistent with what Bob Brody said in his column, Why I Write About My Parents. “We look at our parents in order to see ourselves and even our futures.” By knowing my parents and the lives they lived — maybe I can better know and understand myself and possibly even my children.

I want to meet myself — again.

I think Marlena is very fortunate in that her parent’s lives are well documented. My parents also made rather remarkable journeys. I have finally matured to a point of wishing to know so much more about my them, but all the people who really knew their stories are gone and the detailed documentation that we continue to find about Marlena’s extraordinary parents doesn’t exist.

I am fortunate indeed!

Agreed, Ed. My parents died when I was a young adult with a troubled home life that I didn’t share with anyone…and never got to know as well as I would like. And those who knew them, besides my older sister (who was away as an adult) are gone as well. I regret the missed opportunities to know them better.

Sylvia, I think you hit on something very important. Many of us were over-our-heads trying to manage the chaos of our own young adult lives as our parents were aging. It’s really little wonder we didn’t stop to listen more often than we did. That doesn’t take away from feelings of sadness, but it does ease the guilt.

I had never seen mulberries. Your mother introduced me to them. We went picking one day. I loved them. She made juice and wonderful pastries using them.

Your father let me watch as he performed an appendectomy. I was standing no more than four feet away. He teased me later that I was about to faint. I saw the woman the next day. She was doing well.

I remember the crude tools used during surgery. He used bent table spoons, etc. to hold open the surgery site.

I visited the leper patients who lived on your camp. I remember the tiny lady.

Back home in Steinbach, Manitoba, during the ‘50s, my youth girls’ circle at church , received your mother’s newsletter, so I knew about the work being done by your parents. We read the letter out loud at our meetings.

Oh Lydia, thank you so much for sharing your memories!!! It adds to my emotion about this past week – feeling so close to John and Clara! The “tiny lady.” I love it. Her name was Amalia, and her story is part of the novel we’re writing.

And the bent tablespoons. Wow!

Marlena, my connection with your parents came mainly through my husband John & his parents Hans & Maria Rempel. John’s dad was pastor in Neuland from 1947 to 1959 when they emigrated to Canada. The Rempels had great respect for your parents and their work at Km 81, and continued to exchange mail with them from Canada. Your parents even came to our church Niagara United Mennonite Church to report about their work and visited the Rempels at home. This was part of their adventurous trip by jeep/truck from Paraguay to Canada. Of course, the purpose of the trip was to share their experiences and also collect money for the leprosy mission in Paraguay. I also heard about the Leprastation from my mom who was part of a Frauenverein at NUMC who tore up old sheets to make bandages for Km 81. They rolled miles & miles of bandages as I remember & also sent money to this very important mission, even though many of the women of the group were war widows who were scraping up an existence for themselves and their children. It was a “holy” mission for them! Your parents touched many, many people, and made a world of difference to the leprosy patients of Paraguay!

Kathy, thank you for sharing the lovely memories!

Ha! That Volvo trip from Paraguay to Kansas is described in a chapter of the memoir. I also wrote an essay about it – located in the “Essays” tab of this site, if you’re interested. I think the essay is titled “A Remington and a Volvo” and it should be at the very bottom of the essays list.

I just happened upon a Facebook post that just thrilled me to no end!!! I came here to seek you out and found even more delighted things about your parents. I wish (and pray) that I can find way more to read to even include your book. I pray I can stay connected and know when that is. Prayers for you and your husband as you continue on this journey to share about your parents. Blessings to you! 🙏🕊💙

Debra, thank you so much for your interest, and for posting your note! I feel your support and appreciate it. I will be posting updates here on my website about the release of my memoir, coming out next summer… and the book about my parents’ lives and work as soon as possible after that!